Written by: Cho-Kin Chan (M. Ed., PGDip., B.F.A.) , Theatre Practitioner, Certified Psychodramatist (BPA/UK, HKPA/HK), Drama Therapist (NADTA, US), TSM psychodrama trainee

The Wonderful TSM Wizard of Oz

From Canon of Creativity of Classical psychodrama to TSM Clinical adaptation

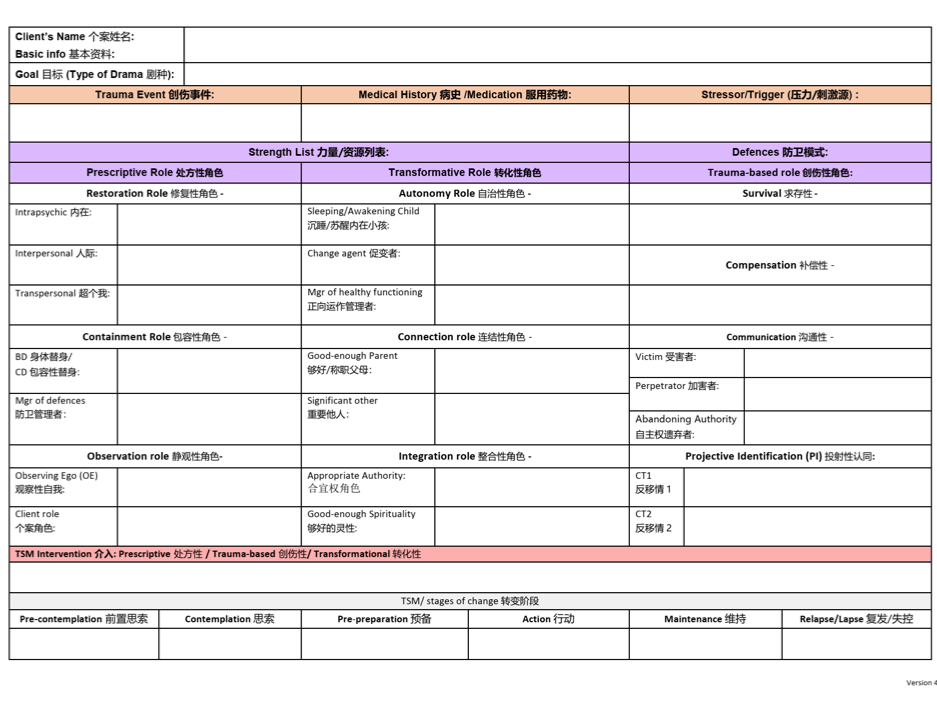

I’d like to tell you a story. The story was about a man (P) who arrived at the Munchkinland in the magical Land of Oz. P seek help from the wizard. Meanwhile, he was looking at his history with the lens of Cannon of Creativity from J.L. Moreno and experienced TSM adaptation of Cannon of Creativity from Dr Kate Hudgins.

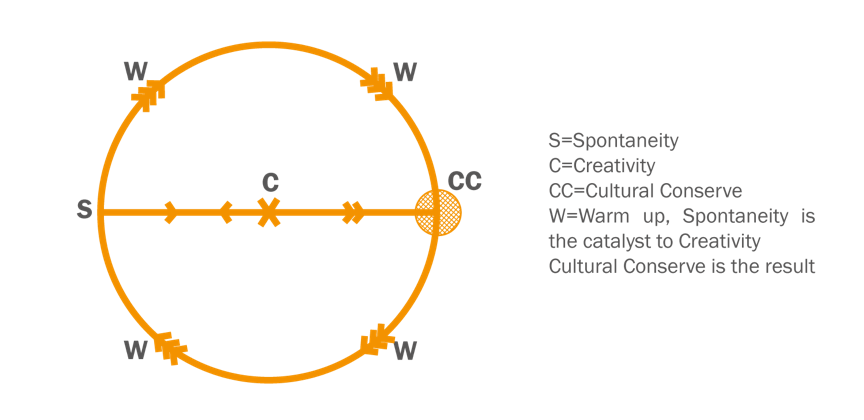

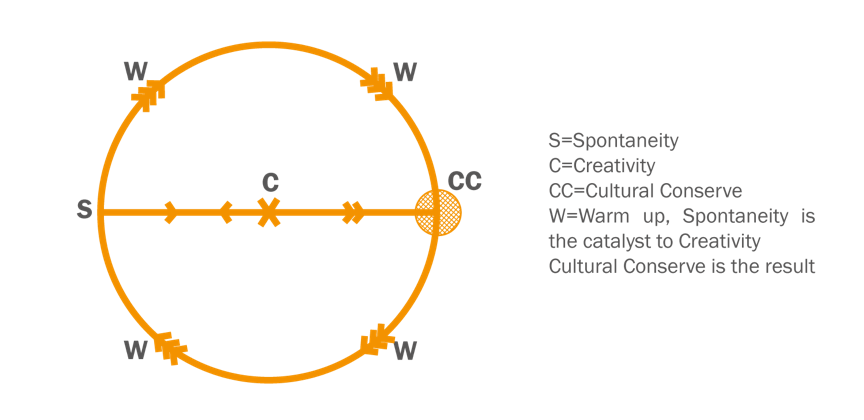

Once upon a time, when P was a child. He witnessed a lot of quarrels and fights from his parents. From time to time, he experienced the unresolved relationship and often held among anger from the authority. He learnt not to express negative feelings, often shows his smiling face or not to feel in his daily life. This coping pattern, or we might say this “Culture Conserve” (CC), was in his life for many years.

One day, P met a young lady, the ballerina from his fantasy, and she was co-working with this guy. He was struck and couldn’t hold his emotion from the flame of love. He couldn’t find the right words when communicating with this lady nor react appropriately when working too close. P tried to hold himself. He was using his energy to suppress the flame and turn himself to numb.

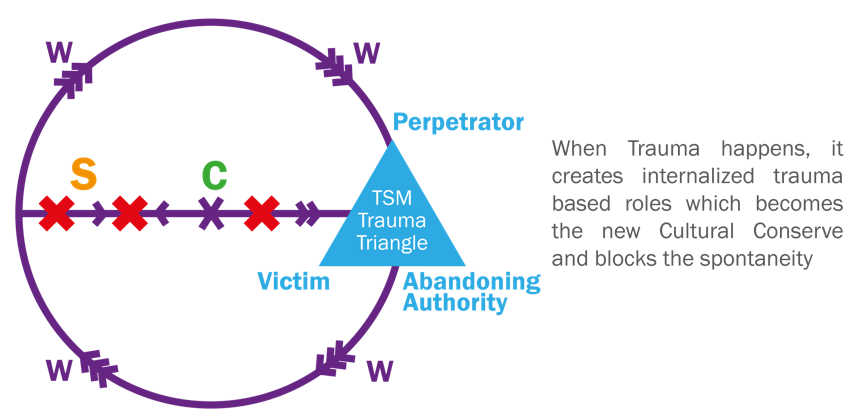

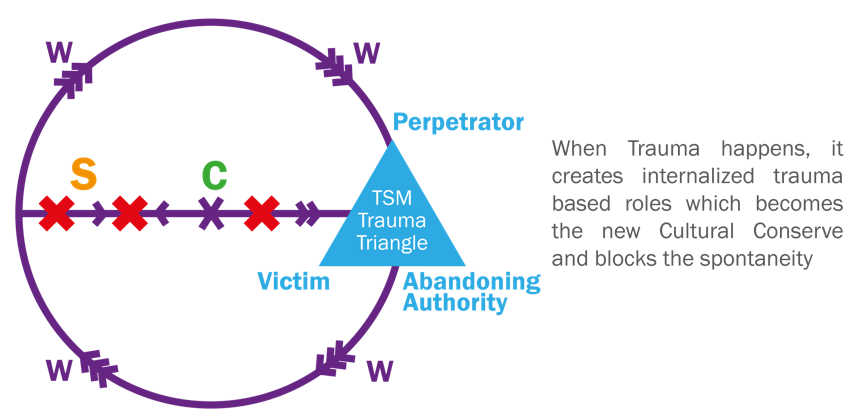

Suddenly, there was a storm. The air in the house was suffocating. The tornado hide the light from the sky. It turned darkness. P was caught up in a cyclone. Meanwhile, he tried hard to open his eyes and he found that there were some images surrounding him. He saw his parents held the TSM trauma roles of perpetrator and abandoning authority. The child self of him was hiding behind the sofa. After watching the scene of his childhood, he reflected on how those experiences turned himself to someone who couldn’t cope well in his intimacy relationship.

It seems that he witnessed how blaming and scolding self was developed in his life. The trauma experience trapped his spontaneity. He wondered if there was no way to resolve it. Although P felt stuck and hopeless, he wants to improve, become more mature, or have a better self for his future, especially for the intimacy relationship. The tornado brought P to the Munchkinland in the magical Land of Oz.

The falling house had killed the Trauma Witch of the East. P was in shock. At that moment, the body of the Trauma Witch of the East disappeared. It remained her voice from the air. She said, “I shall be back!” P was scared and lost.

A TSM wizard (W) arrived in the town and met P.

W said to P, “Let her go away at the moment. I am here with you. What do you want from here?” P wanted to go home.

W brought him a map of OZ.

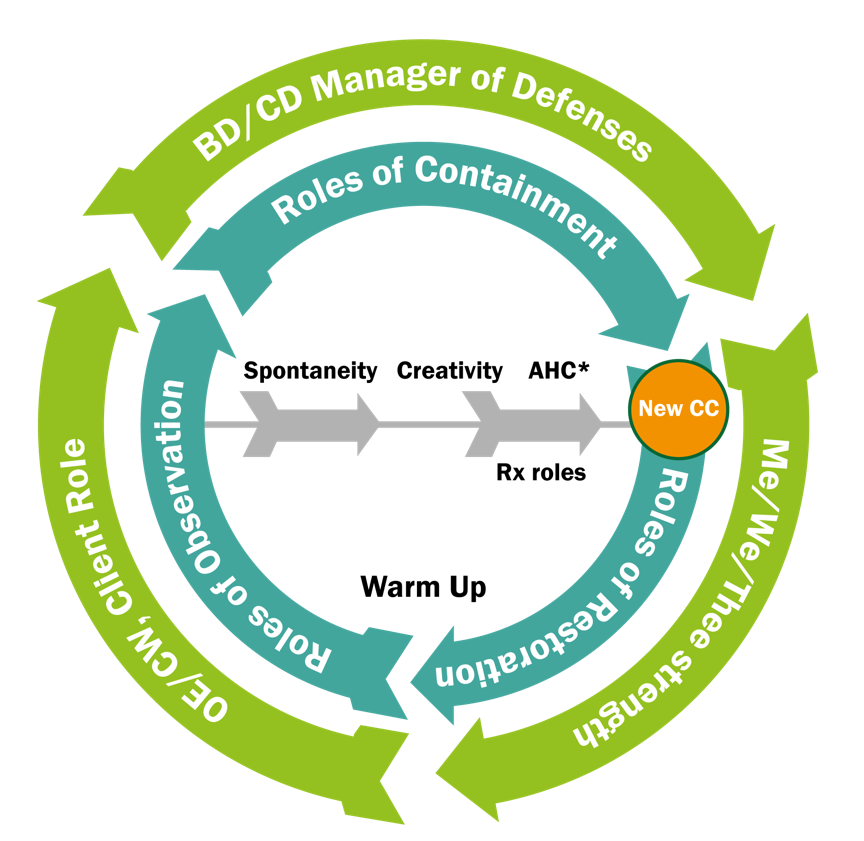

W said to P “P, you should go to see the Powerful Wizard of Oz. He could help. And I like to introduce you a buddy. She is Dorothy (OE), and she is good at observe, support and remind what you need in your journey to OZ.”

P talked to Dorothy about what he wants to achieve in this journey. Dorothy repeated P’s message and supports him in his journey.

Next, W introduced Scarecrow, Tin Man and Lion to P.

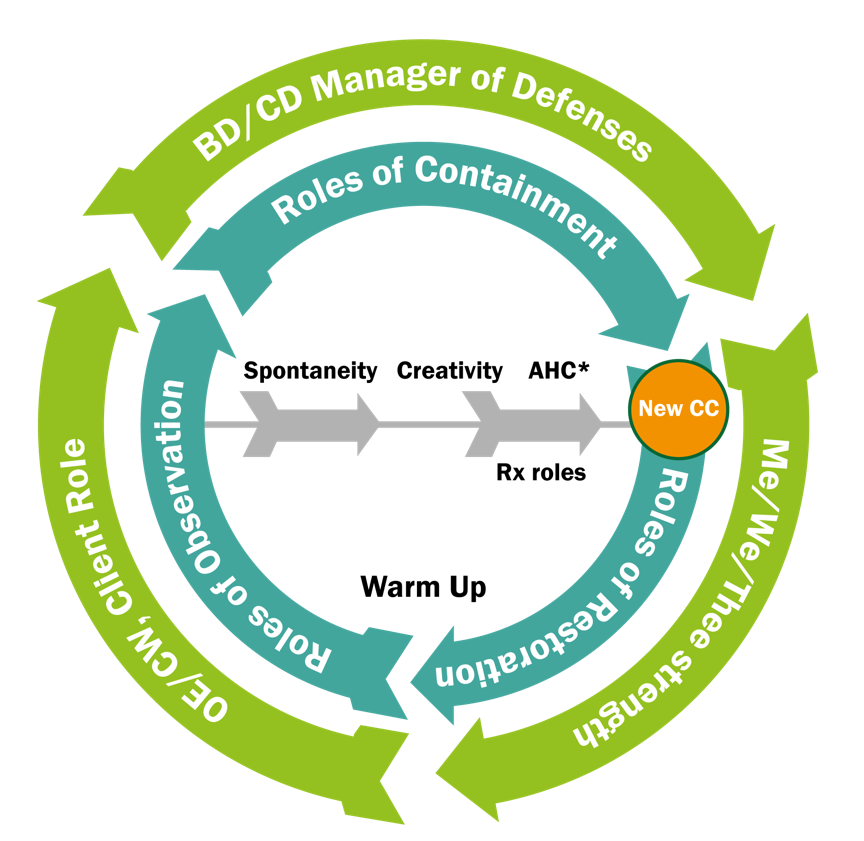

W said, “These 3 buddies had gone through their difficulties and grown. They can support you too.” (Restorative Roles). P started to look at these 3 buddies, and he felt that he has similar quality with them. He associated the wise quality with Scarecrow. The appearance of Tin Man reminded P that he has a supportive relationship with a best friend. When P was looking at the Lion, the sunlight was shining on his fluffy fur. P felt the warm and containing energy from nature. Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tinman, Lion and P started the journey to OZ.

When P stepped on the yellow brick road to OZ, P was shaking with doubt.

“Could I survive this journey? What I should do?”

“Wow….” A little dog called Toto walked to P.

Toto (Roles of Containment) said, “My legs are shaking, and I don’t know if I could survive. I am now putting my feet on the ground and feel the support from the earth. I could take a deep breath slowly, I am with my buddies now. I know it wouldn’t be easy to go to Oz. And I would take the lead in the team with my pace on the yellow brick road.”

Toto’s voice awaked P. He looked at his buddies. P started to realize that he has a lot of support in his journey. He also felt warm and soothing when Toto put his hand on P’s leg. P became energetic, and he put his hand on their shoulder. The team were hopping, skipping, singing and dancing. They created its own rhythm and moving forward to Oz.

The Trauma Witch of the West saw them approaching with her one telescopic eye. She sent a pack of wolves to tear them to pieces, but the Tinman held P’s hand and used his body and axe to protect the team. She sent a flock of wild crows to peck their eyes out, but the Scarecrow and P knew that crow doesn’t like shiny stuff, high voices and noise. They got rid of the crow attack. She summoned a swarm of black bees to sting them, but the Lion brought the team Citronella, Mint, and Eucalyptus plants, which can repel the bees. She sent a dozen of her Winkie slaves to attack them. Dorothy reminded P that he has the team with him. Toto’s helped P in staying awake with a clear mind and felt grounded. P stood firm to repel them.

The interaction of the team warmed P to spontaneously react to the situation. It created a new way to respond to the dangers. P learnt the skills and integrated the element from each buddy to oneself through the Oz journey. He had developed new coping skills, the self-containment and feeling of grounded in his state of mind. The new “Culture Conserve” (CC), had developed with the guidance from TSM wizard.

The Trauma Witch came back again. She brought winged monkeys and caught the team. P knew that he has to help himself and the team to stay conscious and be functional. He throws a bucket of water on himself to remain calm. Fortunately, the water splashed on the Trauma Witch, and she melted away. All the creatures rejoiced at being freed from her tyranny.

P walked into the castle, and he found a little boy. They called him Wizard of Oz. P was curious about him. “What happens to this little boy?”

The little boy was dejected. P kneels down on the floor, held his hands and gave him the comfort. After, the little boy looked at P. The TSM wizard appeared and stood beside P.

W said, “P, did you recognize who the boy is?”

P said, “he was my childhood!”

W said, “what do you want to do with the little traumatized P?”

P guided his team to create a circle of safety. Little P was standing in the middle of them. He observed the team slowly. After, he was smiling. It seemed that he likes to play with each team member. Later, he looked up, stretched his arms and had a deep breath. The team took a deep breath with little P. He was awakening! The air of the space became warm and comfortable.

Instantly, P began whirling through the air, and he fell off his feet on his home town Hong Kong. He felt grounded with confidence. P said, “I’m so glad to be home again. And it is my safety and comfort home!” Years later, he found his ballerina and married her on his birthday!

Adena Bank Lees, LCSW, is a counselor, speaker, author, and consultant, providing fresh perspective on traumatic stress, addiction treatment and recovery. Her specialty is childhood sexual abuse, and in particular, Covert Emotional Incest. She is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker, Licensed Independent Substance Abuse Counselor, Board Certified Expert in Traumatic Stress ®, and a Certified Practitioner of Psychodrama. She is the author of Covert Emotional Incest: The Hidden Sexual Abuse, A Story of Hope and Healing, as well as 12 Healing Steps for Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse; A Practical Guide.

Adena Bank Lees, LCSW, is a counselor, speaker, author, and consultant, providing fresh perspective on traumatic stress, addiction treatment and recovery. Her specialty is childhood sexual abuse, and in particular, Covert Emotional Incest. She is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker, Licensed Independent Substance Abuse Counselor, Board Certified Expert in Traumatic Stress ®, and a Certified Practitioner of Psychodrama. She is the author of Covert Emotional Incest: The Hidden Sexual Abuse, A Story of Hope and Healing, as well as 12 Healing Steps for Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse; A Practical Guide.